healthcare as an "anti-state state"

[A prose version of a twitter thread:]

Understand medicine as a system of social control. It helps explain why healthcare has been a more politically acceptable form of attention to social welfare. Unquestionably medicalization is gentler than criminalization as the focus of the state. But progressive reformers within medicine risk being trapped inside an enclosed system where attention to people’s safety, happiness, and well-being is only politically acceptable if these things are “determinants of health”.

From a governance point of view the ever-growing share of health spending as a share of GDP, reinforces the idea that all other things must then serve the needs of that budget, i.e., we should pay for supportive housing if it leads to savings on health spending, or that in this logic supportive housing “doesn’t work” if it doesn’t efficiently reduce expenditures on health. If homelessness itself was the outcome of interest, supportive housing would “work” or “not work” to the extent it kept people housed and content with their housing.

The underlying logic: people who don’t earn money, in a system where the only way to earn money is to work, must then be sick to merit concern or inclusion. Disability becomes the only basis for guaranteed income and health outcomes the only reason to care about inequity.

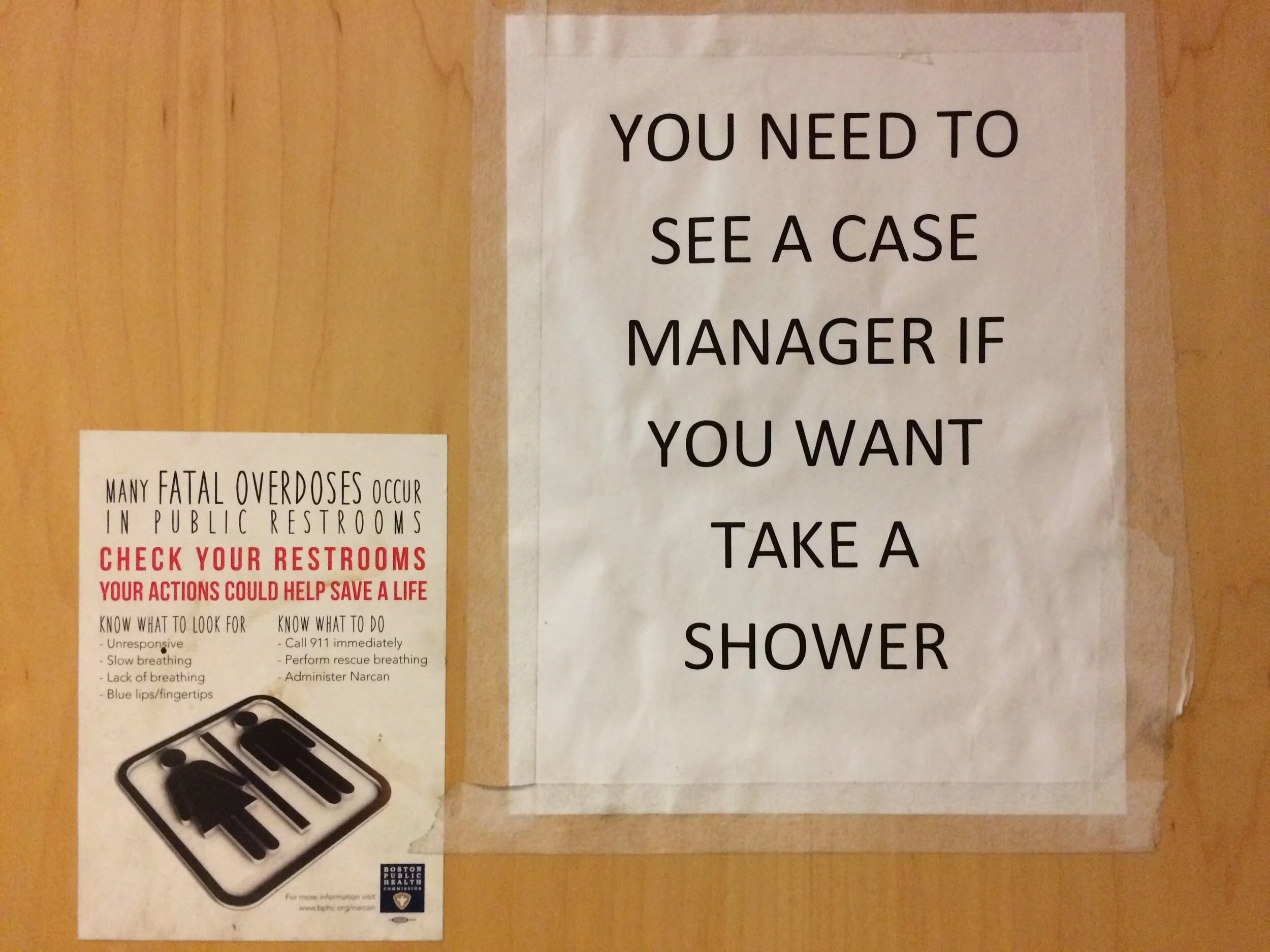

This is of special importance for addiction medicine where we are classifying addiction as a disease in part as a way to remove it from the world of moral judgment and criminalization, but then in essence “owning it” from a social policy point of view.

We should be very cautious about people describing any form of homelessness as a “public health problem” or a problem of “not enough treatment” because these discourses lead ultimately to putting doctors in charge of social policy that is not medical.

A frame of well-being that extends past health would ask why people are homeless and why people use drugs to the point that it creates big problems in their lives and why those two things are related but not at all the same.

Medical people are important but not central if we properly understand overmedicalized forms of mass despair and social abandonment and trauma.

Areas of high degrees of street homelessness, drug use, and impoverishment, are the refugee camps of the adult survivors of a war on children; maintained and amplified by housing as investment instead of social welfare. You can’t medicalize that and do it justice.

On a policy level, the more we medicalize suffering and inequality and responses to trauma, the more we grow the healthcare budget to the point where it becomes what Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes as “the anti-state state”, i.e., an arena of spending and social ideas in which “good deeds” are really a constraint on our imaginations.

For instance: if we cannot pay for practical caring about children, making them feel safe and valued, because a healthcare system spends more and more to attend to the wounds of adult survivors of wounding childhoods.

Healthcare is a necessary component of any society just as some form of social order and protection against violence is also necessary. But when we reflexively view social questions as either medical or criminal, as with addiction, we are really asking, what form of anti-state state will we choose? Rather than asking, what do we all need to make a better world?